Ignore Expected Value, Don't Play Powerball

The Powerball lottery is in the news because the jackpot is up to about $1.5 billion, which sources tell me is a lot of money. The classic stats argument is that you should buy a ticket only if the expected value is greater than the cost of the ticket, which is $2.

Expected value is sum of the value of each possible outcome times the odds of that possible outcome. In this case, it’s the sum of the value times the odds of the 9 ways to win.

| Outcome | Odds |

|---|---|

| $1,500,000,000 | 1 in 292,201,338.00 |

| $1,000,000 | 1 in 11,688,053.52 |

| $50,000 | 1 in 913,129.18 |

| $100 | 1 in 36,525.17 |

| $100 | 1 in 14,494.11 |

| $7 | 1 in 579.76 |

| $7 | 1 in 701.33 |

| $4 | 1 in 91.98 |

| $4 | 1 in 38.32 |

Now there’s also an optional add-on called PowerPlay

, which

will multiply your winnings by a randomly-selected multiplier (except

the jackpot, which remains the same, and the $1 million prize, which

doubles to $2 million). The odds for the multiplier are:

| Multiplier | Odds |

|---|---|

| 5 | 1 in 21.00 |

| 4 | 1 in 14.00 |

| 3 | 1 in 3.23 |

| 2 | 1 in 1.75 |

If you do the math 1, that gives us an expected value of about $5.11 for a standard ticket, and $5.57 for a powerplay ticket. Well good grief! That means we should all go buy a bunch of tickets, right? That’s statistics! We even know not to buy powerplay, because the return isn’t as good!2

Well, no, not really. The problem here is that expected value

is a misleading term. It does not actually tell you what value to expect

for a single ticket.

The expected value here is really just the mean winnings for all possible tickets. But means aren’t helpful here because the distribution is so wildly skewed. Almost all of the expected value—about $4.79—comes from an exact winning ticket.

A better way to get reasonable expectations is with a simulation. I wrote a quick one in Python, which you can find the code for in this Jupyter notebook, and I used it to analyze what we can really expect when playing Powerball.

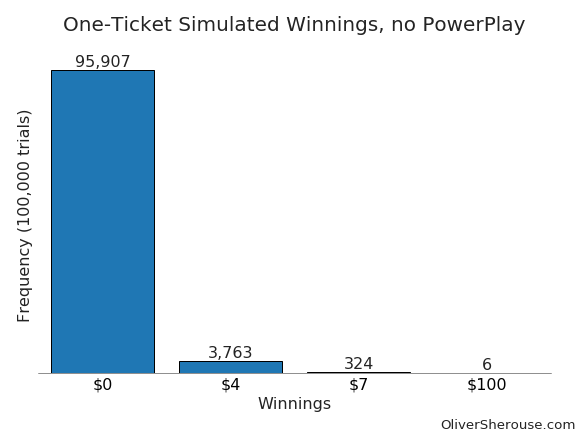

First I ran a simulation of 100 thousand people buying a single

ticket, with no powerplay. How did they turn out?

Well, 95,907 people won exactly jack. 3,763 doubled their money with a four dollar win, while a 324 won the princely sum of seven dollars. A full 6 folks won $100. Woohoo! So if you buy a ticket, what’s reasonable to expect?

Big fat goose egg, that’s what. If you’re really lucky? Four bucks.

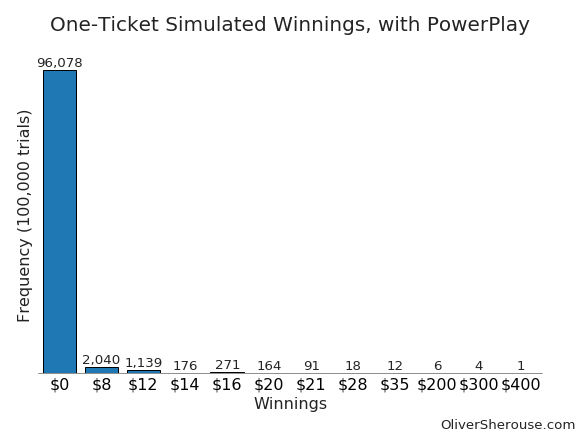

If you add in the PowerPlay, things aren’t much better:

One guy won $400 in 100,000 trials. 96,078 won nothing. Sure, the prizes are bigger, but for the vast majority of cases, you’re just throwing away $3 instead of two.

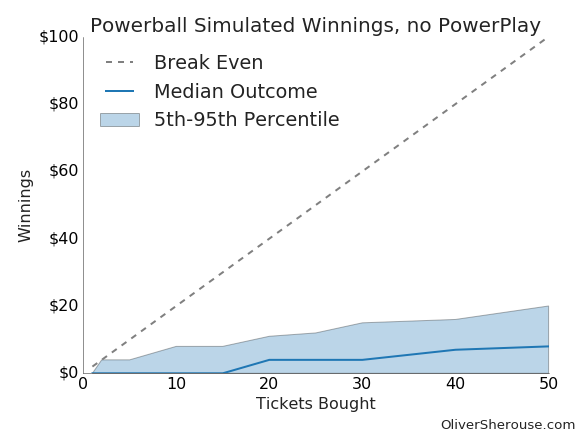

But wait a minute. What if I buy more tickets to improve my odds? That should get me closer to the expected value, right? Well, sort of. Remember, the expected value is dominated by that one winning combo.

I ran the simulation again assuming someone bought, 1, 2, 5, 10, 15,

20, 25, 30, 40, and 50 tickets, with 100,000 trials at each ticket

level. Here’s the results without PowerPlay:

The dotted line means you break even. The solid blue line is the

median outcome, while the shaded area shows the 5th to the 95th

percentile. The winnings you can reasonably expect certainly go up over

time, but they go up slowly—much more slowly than the cost of buying

tickets. Even though you’re getting more wins, you’re generally getting

low-value results and spending a lot on worthless tickest to make it

happen. Even the 95% percentile is earns way below the break-even level

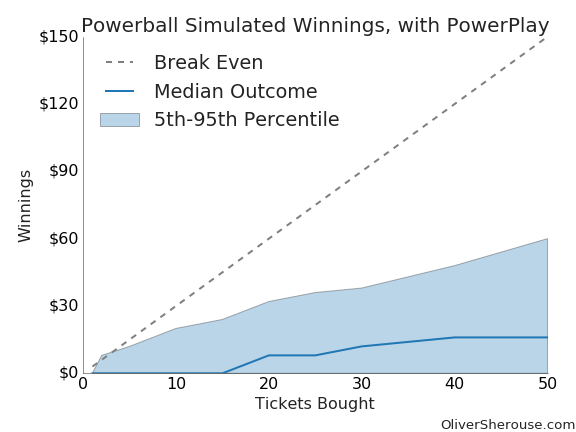

once you get past two tickets. Here’s what it looks like with the

PowerPlay:

Basically the same story here. The upside, 95th-percentile result is

a bit better, but the more realistic median result isn’t. And a bit

better

in this case means you would still lose money, but not

much.

The best median outcome comes from buying one ticket without the PowerPlay option, which is when you just lose $2 and no more. Best feasible result is with the PowerPlay and 2 tickets, where the 95th percentile spent $6 to make $8, the only profit in the 5th to 95th percentile range in the entire simulation.

So what’s the takeaway? First, expected value is overrated for this kind of situation, because you can end up paying too much attention to rare, extreme possiblities. Running a Monte Carlo simulation like the one above gives you more realistic guidance. Expected value may be appropriate for large organizations where you do so many analyses that the one-in-a-million shot actually shows up every now and then, but they’re less suited to one-shot decisions.

But second, and more directly, don’t play Powerball. The lottery is

still a tax on people who are bad at math. And people who tell you that

the statistics say otherwise have not thought all the way through their

statistics. All the math not in the post can be seen in this Jupyter

notebook↩︎ Actually, I’m being a bit lazy here. Alex Tabarrok has

an excellent post

explaining why the expected value is a good bit lower than the simple

analysis suggests, but that’s beside the point I’m making.↩︎